Photojournalism has never simply been about pictures. It has been about proof. It has been about us.

Over the next twelve months, Wobneb Magazine will strive to feature contemporary photojournalism that is meaningful and powerful. Whether the work is loud or quiet, it should have a clear voice.

If you are a photographer or photojournalist committed to telling stories that inform, clarify, and hold truth to power, we want to see your work. Submit your projects for consideration at wobneb magazine, or tag and follow me on Instagram @wobnebmag so your images can be seen and shared with a wider community of engaged viewers. The next essential story may already be in your archive, on your SD — or just beyond your lens.

Since the 1960s, as modern news media began to accelerate in reach and influence, photography moved from illustration to evidence. Images no longer just accompanied the story — they were the story. A single frame could compress politics, power, grief, resistance, and history into something immediate and undeniable. In an era when public trust is constantly negotiated, that role has only grown more urgent.

The maturation of news media over the last six decades is inseparable from the evolution of photojournalism. In the 1960s and 70s, photographs from Vietnam, the Civil Rights Movement, and anti-war protests reshaped public opinion in ways written reports alone could not. These were not abstract policy debates; they were children running from napalm, marchers facing police dogs, soldiers exhausted in the mud. The camera brought distant realities into living rooms, forcing viewers to confront the human cost of political decisions. Photojournalism became a bridge between experience and awareness between power and the public.

As media expanded through satellite broadcasting, 24-hour news cycles, and eventually the internet, the pace of image circulation exploded. But the mission at the core of photojournalism did not change: make the opaque visible. Whether documenting famine, economic collapse, migration, environmental disaster, or war, photojournalists work in the space where complexity lives. Their job is not simplification; it is clarification. They translate murky, layered, often deliberately obscured situations into visual records that resist erasure.

By the 1990s and early 2000s, digital technology transformed both the production and distribution of images. News moved faster. Audiences grew global. Barriers to entry lowered. At the same time, the authority of the image became more contested. Editing tools, image manipulation, and later algorithmic distribution challenged the assumption that “the camera doesn’t lie.” In this environment, ethical photojournalism became even more critical. Captioning, context, and transparency in process emerged as essential components of credibility. The photograph alone was no longer enough; the framework around it mattered just as much.

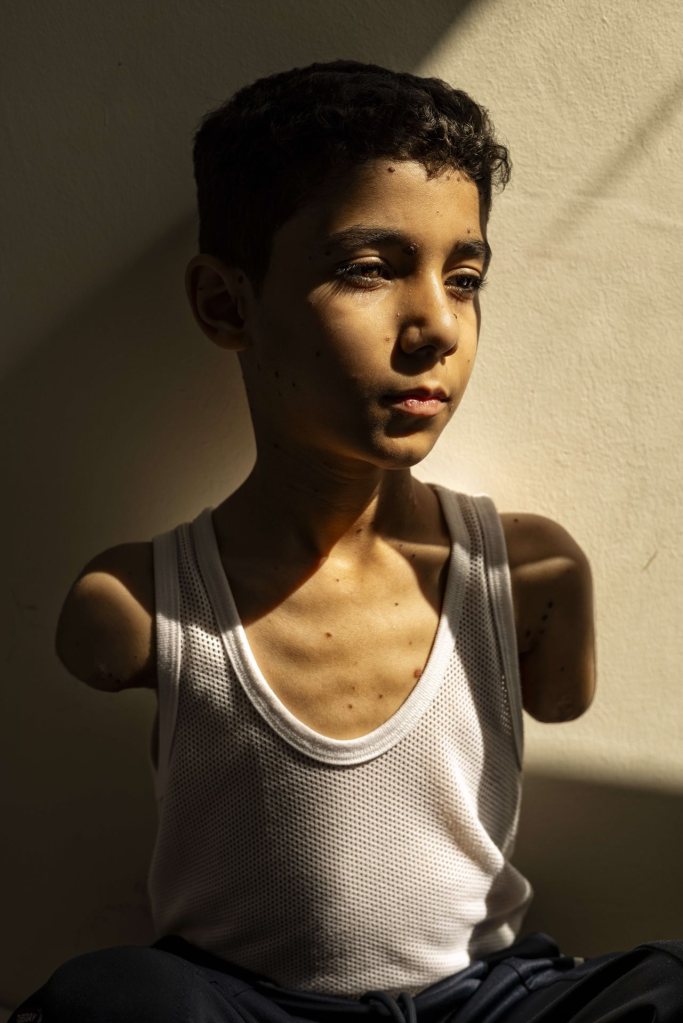

Telca, El Salvador. 2022

The 2010s brought social media, citizen journalism, and real-time image sharing from nearly every corner of the world. This democratization of visual reporting expanded what we could see — but also what could be distorted. In a feed-driven media ecosystem, images compete for attention, stripped of nuance and often detached from origin. Here, the trained photojournalist plays a distinct role. They are not only witnesses but verifiers. They understand the responsibility of proximity: to subjects, to events, and to consequences. Their work is grounded in relationships, research, and risk — not just access to a camera.

Now, in 2026, we face an era defined by information overload, AI-generated imagery, and deepfakes that can convincingly fabricate realities. Paradoxically, this makes documentary photography more vital, not less. Trust in institutions may fluctuate, but the need for reliable visual testimony remains constant. The photojournalist stands as a counterweight to manipulation, operating with professional standards that insist on accuracy, accountability, and respect for those being photographed.

Crucially, photojournalism does not only inform — it holds power to account. Governments, corporations, and institutions often prefer opacity. Photojournalists work in the opposite direction. They document environmental damage that might otherwise go unseen. They reveal the human impact of policy decisions buried in bureaucratic language. They show who benefits, who suffers, and who is left out of the frame of official narratives. In doing so, they contribute to a public record that cannot be easily rewritten.

But the impact of photojournalism is not measured solely in moments of crisis. It also lives in sustained attention. Long-term projects on housing, labor, healthcare, education, and community life build visual archives that challenge stereotypes and add texture to public understanding. These bodies of work remind us that “news” is not only what erupts, but what persists.

For audiences deeply engaged with photography, the question is not whether images matter — it is how we choose to engage with them. Do we slow down long enough to read the caption, understand the context, and consider the photographer’s position? Do we recognize the labor, access, and ethical decisions behind the frame? Supporting serious photojournalism means valuing not just the image, but the process and responsibility that produced it.

The work demands curiosity, empathy, patience, and a commitment to accuracy that extends beyond aesthetics. It requires the courage to stand in difficult places and the humility to represent others’ realities with care.

Photojournalism’s history since the 1960s shows us one thing consistently: when the public can see clearly, conversations change. Policy shifts. Narratives are challenged. Memory is preserved.

That work is far from finished.